MINIMALLY INVASIVE MITRAL VALVE REPLACEMENT

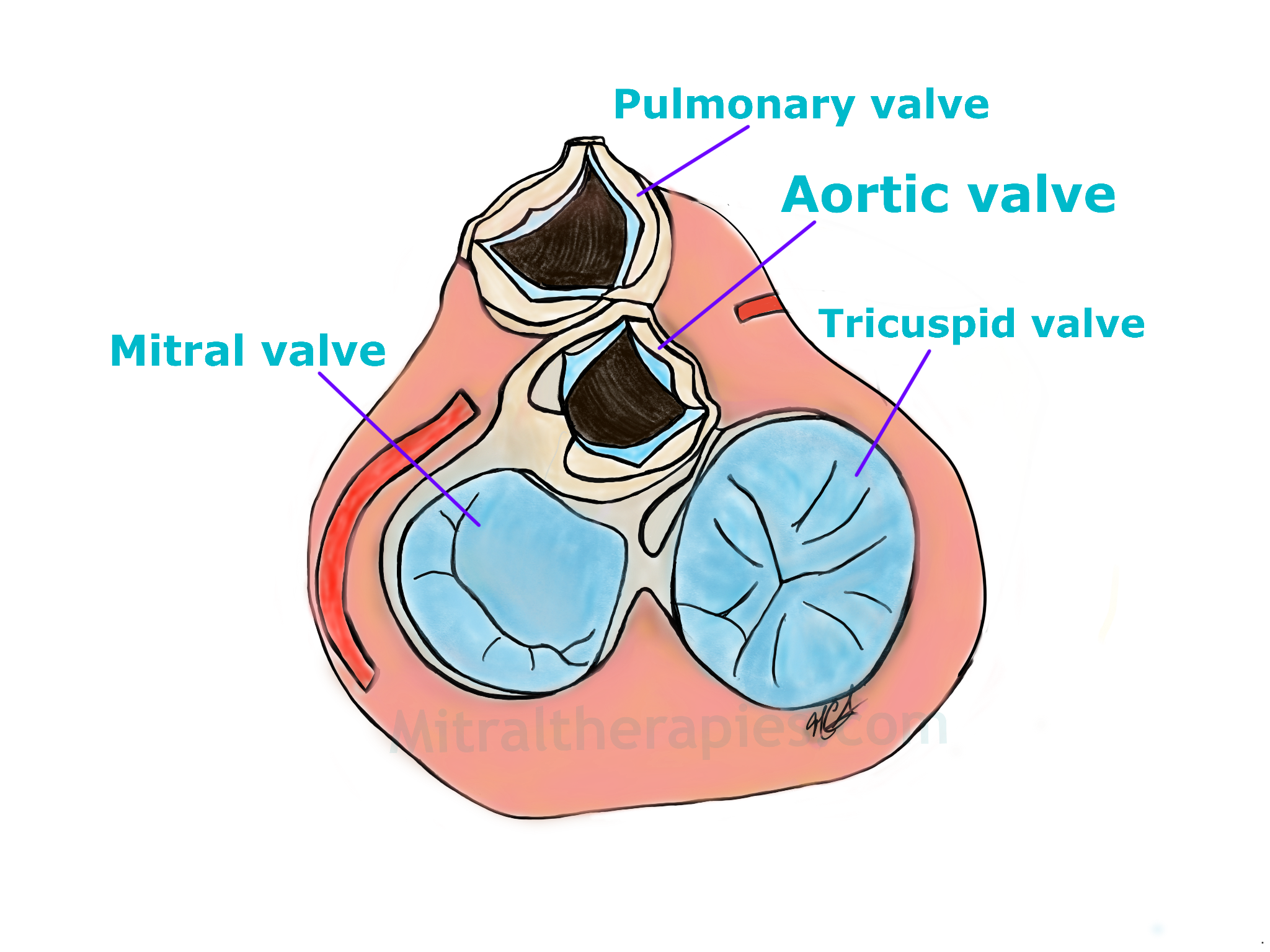

The bottom part of the heart seen from above. To the left in light blue is the mitral valve with typical C shape configuration and to the right is the tricuspid valve. Between the two large valves at the top is the aortic valve and above it the pulmonic valve.

The decision to replace a mitral valve may have to do with the durability of a repair of a particular valve, the medical condition of the patient and the acuity (emergency) of the circumstances. In general, if a valve needs to be replaced there are two choices, a carbon based valve (mechanical) and a tissue (bioprosthetic valve). Within the bioprosthetic valves there are porcine (the actual valve of a pig) and bovine (manufactured from the heart sac of a cow).

Different companies manufacture mechanical valves, but today they all have the same overall mechanism, two tilting semicircles that open and close based on pressure differentials. These valves require that the patient take warfarin (an oral blood thinner medication) for life to maintain the valve from clotting off, a circumstance that could cause strokes or embolic events to other parts of the body. In general, these valves last decades provided ideal circumstances are met of good anticoagulation and avoidance of infection.

Images of mitral valve replacements. To the left a bioprosthetic valve made of the heart sack of a cow (bovine pericardium) and to the right a mechanical valve form graphite. The choice to replace a mitral valve is made only after the determination that a repair is not possible or that it would lead to a less than durable repair.

Take Home Points:

Mitral valve replacements can be ‘biological’ or ‘mechanical’ valves.

All mitral valve replacements can be performed minimally invasive.

Mitral valve replacements are reserved for circumstances where repair is not possible.

Bioprosthetic valves started with the porcine valve and later branched out to the bovine pericardial valves. These valves are overall very durable when implanted in the right patients. Perhaps the biggest determinant of eligibility to these valves is the age. Patients younger than 65 years of age should be considered and counseled on mechanical valves, whereas those 65 years of age or older should be considered and counseled for bioprosthetic valves. This is not a rule set in stone, but rather a guideline to medical practice. Other factors such as occupation also play a role in the decision of which valve to select. Patients with high-risk occupations should not receive mechanical valves. Such occupations may involve contact sports, competitive race car driving, high risk construction work.

Mitral valve replacement with severe Mitral Annular Calficiation

Mitral Valve Replacement for Severe Bacterial Endocarditis (Infection)

Transcatheter mitral valve-in-valve replacement

In the last three years the Food and Drug Administration approved the use of a transcatheter valve designed for use in the aortic position to be implanted in the mitral position within a pre-existing surgical mitral valve. The rationale for this procedure performed via the right femoral vein (with a puncture in the groin) is to help patients with prior mitral valve replacements who have high risk for a repeat mitral valve operation. The procedure is performed under general anesthesia and without the need for the heart-lung machine. The durability of this procedure and of the transcatheter valve in the mitral position is not known.

One Therapy not approved by the FDA (Experimental) is Worth Talking About

Direct TAVR in MAC… (surgical transcatheter aortic valve in mitral annular calcification)

Mitral annular calcification is a severe problem involving the mitral valve in which the annulus of the valve (frame of the french doors) suffers severe calcium deposition over the years. This calcium leads to stiffness and often times involves the flaps (leaflets) of the valve. MAC, as surgeons and cardiologists know this problem, is perhaps the final frontier in mitral valve care.

The original surgical solution to this is to replace the valve by resecting or cutting the entire calcium bar which typically accumulates in the posterior annulus (posterior frame). This operation was pioneered by one of cardiac surgery’s master surgeons Professor Tirone David. The procedure is risky and because of this surgeons looked for an alternative with newer technologies. The TAVR in MAC holds the promise to be the answer for this cases.

In this procedure a balloon expandable TAVR valve designed for the aortic position is implanted within the calcium frame of the mitral valve during open heart surgery performed whether by sternotomy or minimally invasive approach.

The outcomes with this non-FDA approved procedure have been positive according to case series and case reports, and is only performed in certain centers across the United States. Although we are not advocating that for this procedure, persons with severe mitral leakage or tightening should investigate it further as the alternatives to this are high risk.

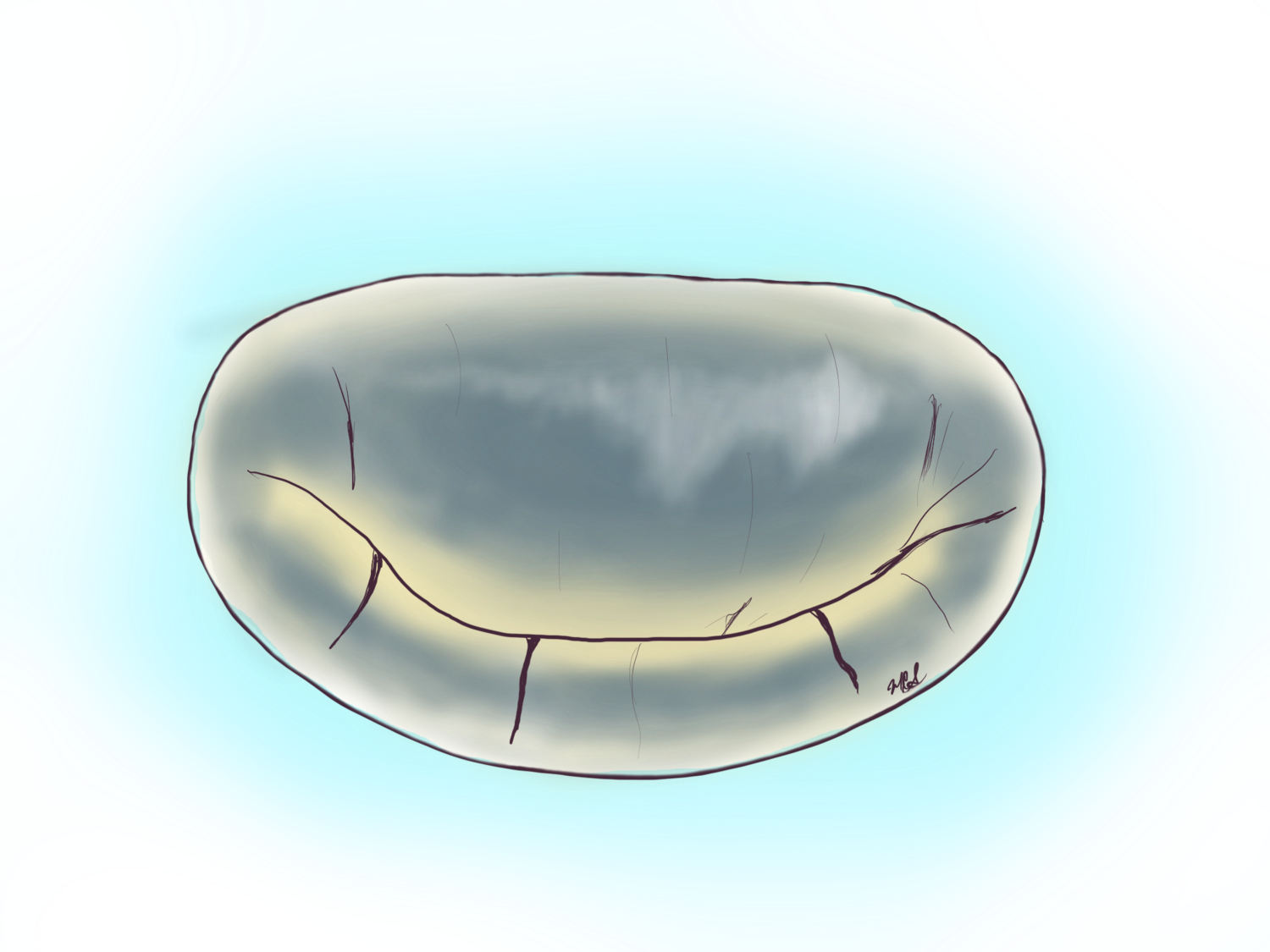

An intraoperative picture of the mitral valve with two things happening. First it has a clip in the middle holding the two flaps together. Second, it has severe MAC or mitral annular calcification from the top left corner to the top right corner of the image. This calcium makes it difficult and risky to replace the valve in the conventional fashion.

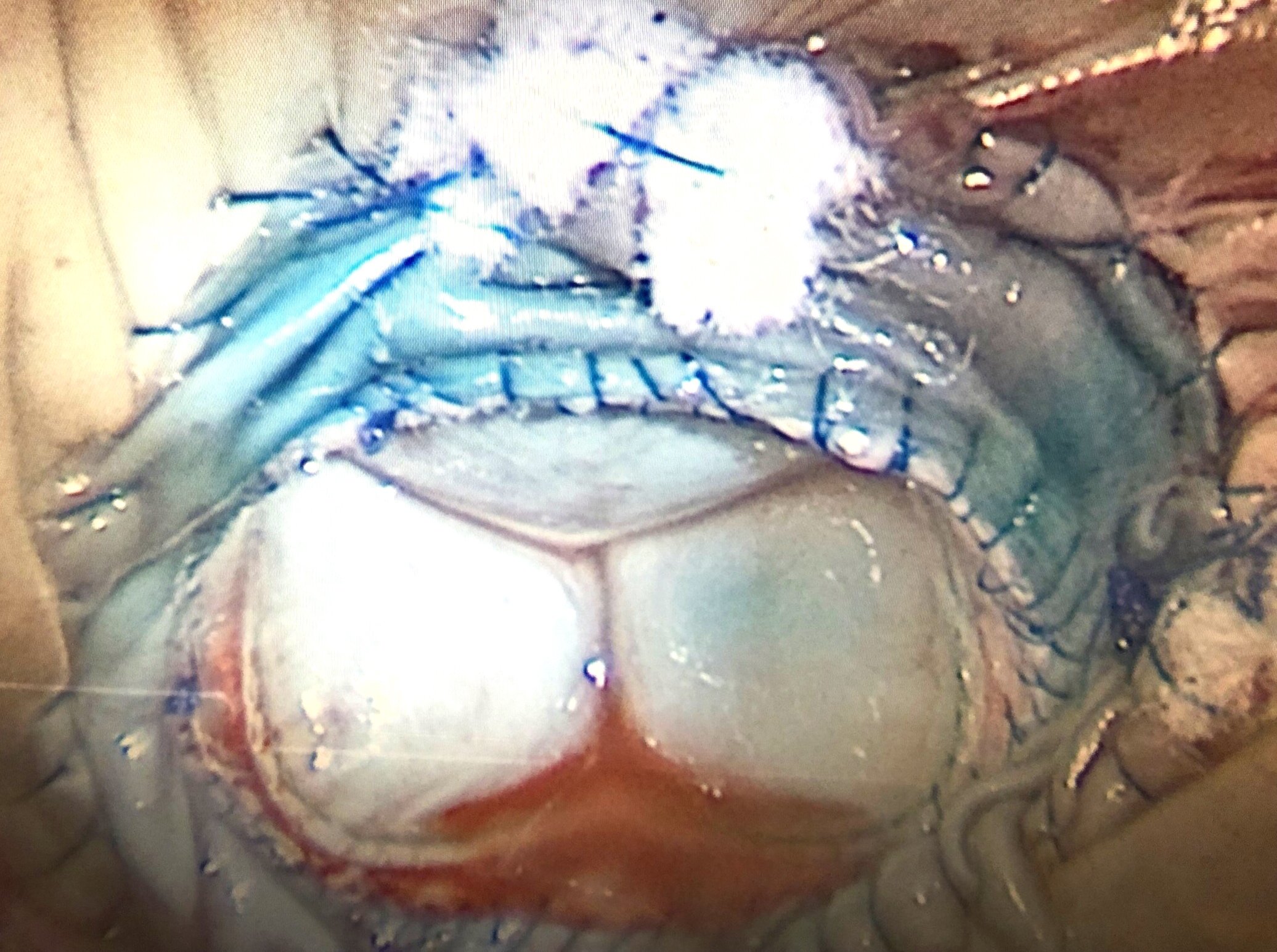

This is the picture of the final product of a TAVR in MAC. The valve seen in place is a transcatheter aortic valve balloon expandable. This was implanted within the calcium of the mitral annulus.